Entropy & the Lost Art of Disorder

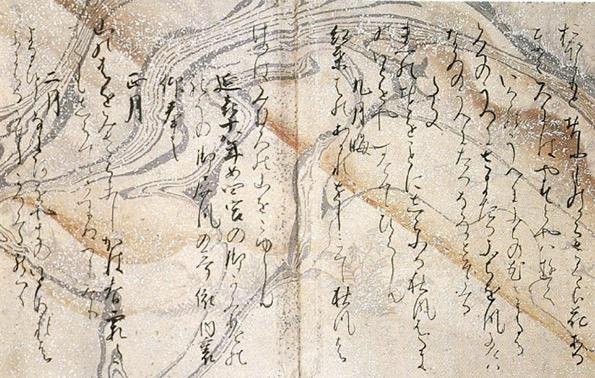

Japanese marbling, or Suminagashi, was practiced in early 12th Century Japan, the art is created through dripping black or blue ink onto a surface of water, a marbling effect is then created through the movement of the water, the breeze in the room, or the artist blowing against the water’s surface creating random swirls of patterns which are then imprinted onto paper.

In the 15th Century, marbling made its way to Turkey and Persia, where new methods were developed with gauche and oil paints. combs were brushed through the patterns on the water, the thickness of the paints used along with the tools meant that the artists had more control over the patterns they were creating. Though the obsession with retaining control over the marbling would eventually become its downfall. Pictured below is the finish of a book from London 1860 where the brush technique has been used.

The unique finish of marbled paper became popular throughout Europe by the 17th Century, with marbled paper being manufactured in England, France, Holland, Italy, and Germany, however the tricks of the trade were kept a closely guarded secret and marbled paper was highly sought after by book binders who wished to use it as endpapers.

Unfortunately, people’s obsession with perfection and the high demand for marble finished paper pushed the industry towards the overmechanisation of marbling. By the 19th Century, marbling machines were invented, and a company owned by Alois Dessauer in Aschaffenburg became the largest producer of decorated paper in the world.

The disorder and entropy of paper marbling which made it so unique gave way to mass mechanised production, as profits were prioritised over the art of slow craft, the secrecy of the art form and its following became diminished as the once highly sought after material became overabundant in factory made replications.

Inversely, charcoal garnered a reputation for being a preliminary art form, employing the medium for quick sketches, it is one of the earliest drawing materials with evidence of its use in prehistoric caves and throughout Ancient civilisations. It gained popularity throughout the Renaissance period as it was applied with academic studies of human anatomy.

Charcoal’s journey throughout history acts as a counterpart to paper marbling, with charcoal first gaining popularity for the control the artist had over depicting accurate sketches during the Renaissance, and throughout history as a sketching tool for realistic paintings from Baroque to Romanticism, to then be used in a way which was more abstract and free during the late 19th Century Expressionist period.

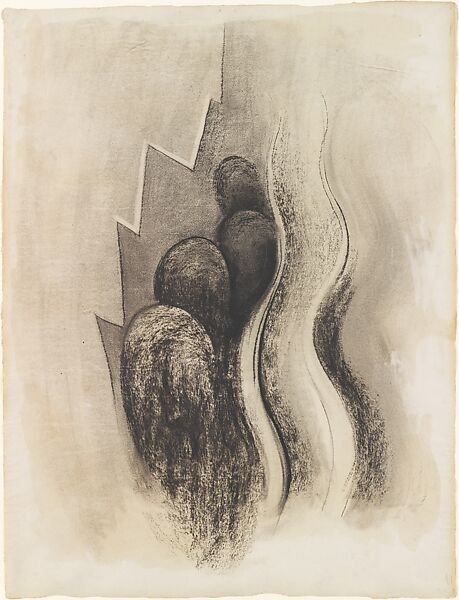

Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘Drawing Xiii’ represents a departure from the, historically, academic usage of charcoal in art, with it primarily being used to depict accurate renderings of the human figure with Da Vinci and Michelangelo both utilising the medium for more anatomical work.

O’Keeffe’s style was a breakaway from the norm and a stark contrast to the traditional charcoal sketches. She instead chose to use the medium to express the undulating flow of nature.

Natalie Stopka talks about ‘relinquishing control’ in your work when it comes to Suminagashi, and I think that’s something incredibly important in a digital era, we can take our art too literally and seriously and oftentimes approaching our work with a predetermined ideology of what the output will look like can inhibit our creative abilities to be experimental and playful.

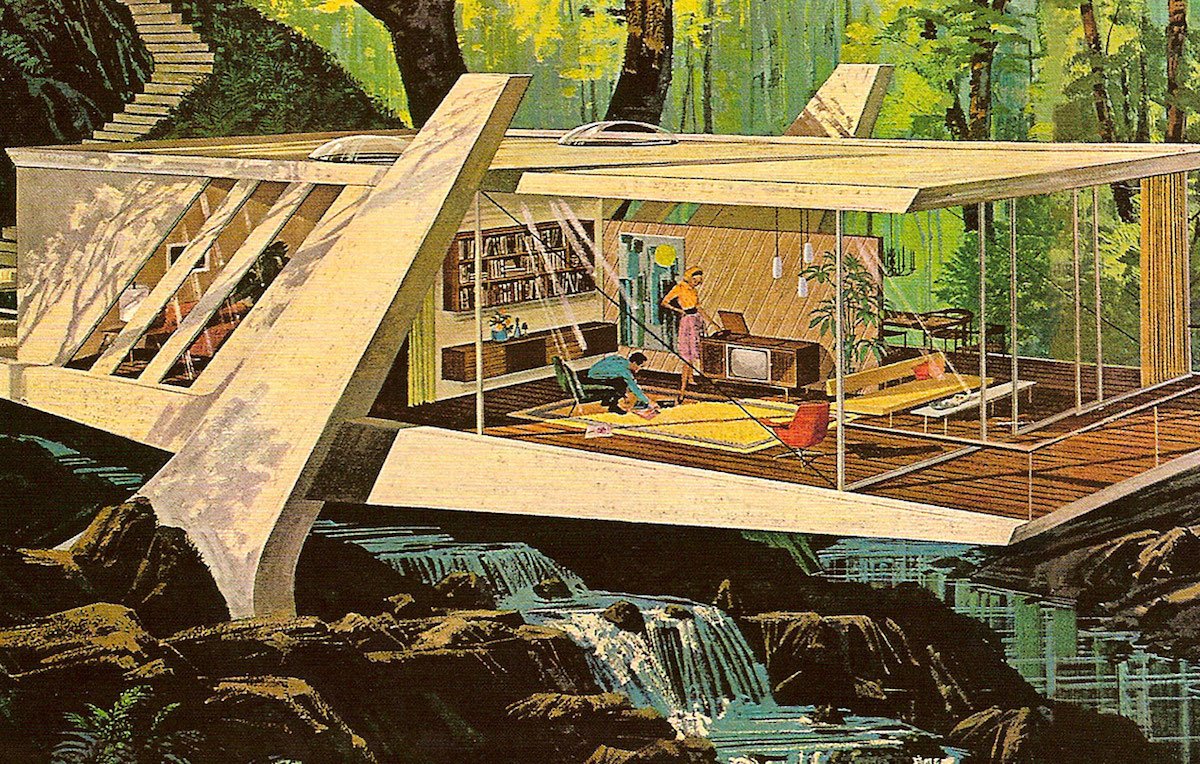

Annie Hogg sources materials from the outdoors to char and use as paints, inks and even sculptural work and states that the materiality of the pigment source is of great importance within the subsequent work.

Pictured here ‘'she' touches hag & is transformed by timelessness & infinite space’ from the series ‘Blood Bone Rust & Stone’ 2022, it is made from Beara earth pigments, mine rust, votive charcoal of holly branch, peat and snail shell.

What outcomes can we create when we enable experimentation to take the forefront of our practice and allow the materials to guide us?