Reconciling with Nature in our Built Environment.

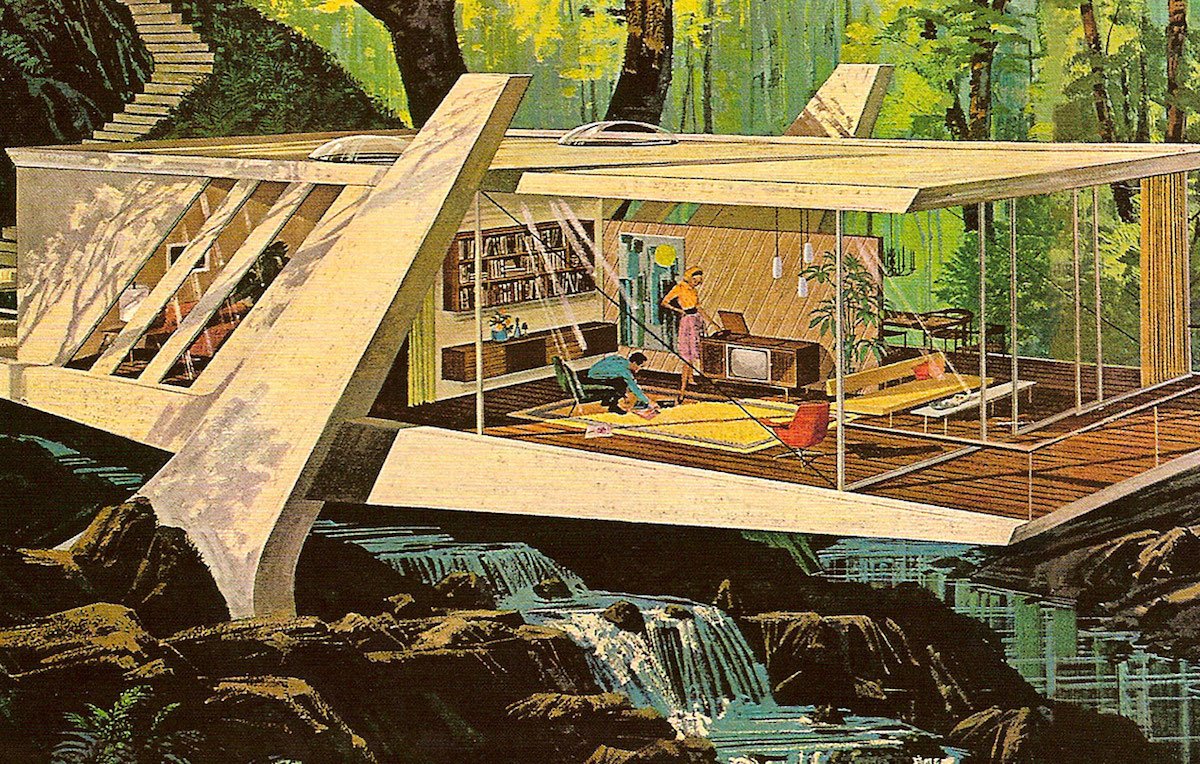

Charles Schridde’s Illustration for Motorola’s ‘House of the Future’ Campaign, first published in Life Magazine 1961.

The 1960’s brought with it a postwar economic boom, it was a time venerated for its hopeful optimism, and as depicted in Schridde’s work for the Motorola ad campaign, a time to ruminate over what the future might bring. The 1960’s brought with it a playfulness in designs as commercial artists began to experiment with the wonder material that was plastic.

Schridde's retro futuristic paintings depict an idyllic life where humans and nature live more harmoniously, allowing structures to follow the form of the environment they reside within.

A reconciliation with nature is something often considered in any media depicting utopian or idyllic futures, to rekindle our once symbiotic relationship is a dream that many have pondered, but how did we stray so far from our roots in the first place, to a point where our built environment has created a veiled curtain for us to trick ourselves into believing that we live separately from nature.

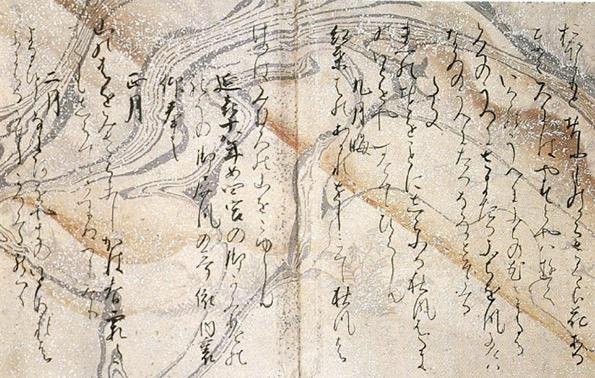

The Romanticism movement was a rejection of the status quo, often depicting people enjoying serene and peaceful moments and aiming to exemplify the beauty of nature. It’s no wonder then that this movement came about at the height of the Industrial Revolution. The image here from 1818 by Caspar David Friedrich titled Wanderer above the Sea of Fog can be used as an example of the yearning for the outdoors people of the time may have felt as structures and enterprises rapidly grew around them.

The industrial revolution saw the mechanisation of agriculture, further disconnecting us from our source of nourishment as we shelter within our built environment, and with it an ancient knowledge of foraging and identifying organisms is being lost in history as we grow accustomed to gathering our sustenance from shop shelves, losing our once symbiotic connection to plant life.

Our current disconnect from nature encourages extractivist and consumerist lifestyles. Convincing others to empathise with the natural environment can be a hard sell when many go their daily lives feeling entirely separate from it.

So, how can we reconnect? Well, just like the art of slow practice, we can adjust and refute the fast paced life that the industrial revolution thrust upon us and instead opt to grow and forage our own produce, regaining the knowledge and respect for our nourishment which our hunter gatherer ancestors once held.

Harari writes in his book Sapiens that “our brains and minds are adapted to a life of hunting and gathering. Our eating habits, our conflicts and our sexuality are all the result of the way our Hunter gatherer minds interact with our current post-industrial environment, with its mega-cities, aeroplanes, telephones and computers.

This environment gives us more material resources and longer lives than those enjoyed by any previous generation, but it often makes us feel alienated, depressed and pressured.” and whatever your thoughts on that are, there’s certainly something rewarding in foraging for, or nurturing your own nourishment!